Boolean algebra (logic)

Boolean algebra (or Boolean logic) is a logical calculus of truth values, developed by George Boole in the 1840s. It resembles the algebra of real numbers, but with the numeric operations of multiplication xy, addition x + y, and negation −x replaced by the respective logical operations of conjunction x∧y, disjunction x∨y, and negation ¬x. The Boolean operations are these and all other operations that can be built from these, such as x∧(y∨z). These turn out to coincide with the set of all operations on the set {0,1} that take only finitely many arguments; there are 22n such operations when there are n arguments.

The laws of Boolean algebra can be defined axiomatically as certain equations called axioms together with their logical consequences called theorems, or semantically as those equations that are true for every possible assignment of 0 or 1 to their variables. The axiomatic approach is sound and complete in the sense that it proves respectively neither more nor fewer laws than the semantic approach.

Contents |

Values

Boolean algebra is the algebra of two values. These are usually taken to be 0 and 1, as we shall do here, although F and T, false and true, etc. are also in common use. For the purpose of understanding Boolean algebra any Boolean domain of two values will do.

Regardless of nomenclature, the values are customarily thought of as essentially logical in character and are therefore referred to as truth values, in contrast to the natural numbers or the reals which are considered numerical values. On the other hand the algebra of the integers modulo 2, while ostensibly just as numeric as the integers themselves, was shown to constitute exactly Boolean algebra, originally by I.I. Zhegalkin in 1927 and rediscovered independently in the west by Marshall Stone in 1936. So in fact there is some ambiguity in the true nature of Boolean algebra: it can be viewed as either logical or numeric in character.

More generally Boolean algebra is the algebra of values from any Boolean algebra as a model of the laws of Boolean algebra. For example the bit vectors of a given length, as with say 32-bit computer words, can be combined with Boolean operations in the same way as individual bits, thereby forming a 232-element Boolean algebra under those operations. Any such combination applies the same Boolean operation to all bits simultaneously. This passage from the Boolean algebra of 0 and 1 to these more general Boolean algebras is the Boolean counterpart of the passage from the algebra of the ring of integers to the algebra of commutative rings in general. The two-element Boolean algebra is the prototypical Boolean algebra in the same sense as the ring of integers is the prototypical commutative ring. Boolean logic as the subject matter of this article is independent of the choice of Boolean algebra (the same equations hold of every nontrivial Boolean algebra); hence, there is no need here to consider any Boolean algebra other than the two-element one. The article on Boolean algebra (structure) treats Boolean algebras themselves.

Operations

Basic operations

After values, the next ingredient of any algebraic system is its operations. Whereas elementary algebra is based on numeric operations multiplication xy, addition x + y, and negation −x, Boolean algebra is customarily based on logical counterparts to those operations, namely conjunction x∧y (AND), disjunction x∨y (OR), and complement or negation ¬x (NOT). In electronics, the AND is represented as a multiplication, the OR is represented as an addition, and the NOT is represented with an overbar: x ∧ y and x ∨ y, therefore, become xy and x + y.

Conjunction is the closest of these three to its numerical counterpart, in fact on 0 and 1 it is multiplication. As a logical operation the conjunction of two propositions is true when both propositions are true, and otherwise is false. The first column of Figure 1 below tabulates the values of x∧y for the four possible valuations for x and y; such a tabulation is traditionally called a truth table.

Disjunction, in the second column of the figures, works almost like addition, with one exception: the disjunction of 1 and 1 is neither 2 nor 0 but 1. Thus the disjunction of two propositions is false when both propositions are false, and otherwise is true. This is just the definition of conjunction with true and false interchanged everywhere; because of this we say that disjunction is the dual of conjunction.

Logical negation however does not work like numerical negation at all. Instead it corresponds to incrementation: ¬x = x+1 mod 2. Yet it shares in common with numerical negation the property that applying it twice returns the original value: ¬¬x = x, just as −(−x) = x. An operation with this property is called an involution. The set {0,1} has two permutations, both involutary, namely the identity, no movement, corresponding to numerical negation mod 2 (since +1 = −1 mod 2), and SWAP, corresponding to logical negation. Using negation we can formalize the notion that conjunction is dual to disjunction via De Morgan's laws, ¬(x∧y) = ¬x ∨ ¬y and ¬(x∨y) = ¬x ∧ ¬y. These can also be construed as definitions of conjunction in terms of disjunction and vice versa: x∧y = ¬(¬x ∨ ¬y) and x∨y = ¬(¬x ∧ ¬y).

Figure 2 shows the symbols used in digital electronics for conjunction and disjunction; the input ports are on the left and the signals flow through to the output port on the right. Inverters negating the input signals on the way in, or the output signals on the way out, are represented as circles on the port to be inverted.

Derived operations

Other Boolean operations are derivable from these by composition. For example implication x→y (IMP), in the third column of the figures, is a binary operation which is false when x is true and y is false, and true otherwise. It can be expressed as x→y = ¬x∨y (the OR-gate of Figure 2 with the x input inverted), or equivalently ¬(x∧¬y) (its De Morgan equivalent in Figure 3). In logic this operation is called material implication, to distinguish it from related but non-Boolean logical concepts such as entailment and relevant implication. The idea is that an implication x→y is by default true (the weaker truth value in the sense that false implies true but not vice versa) unless its premise or antecedent x holds, in which case the truth of the implication is that of its conclusion or consequent y.

Although disjunction is not the exact counterpart of numerical addition, Boolean algebra nonetheless does have an exact counterpart, called exclusive-or (XOR) or parity, x⊕y. As shown in the fourth column of the figures, the exclusive-or of two propositions is true just when exactly one of the propositions is true; equivalently when an odd number of the propositions is true, whence the name "parity". Exclusive-or is the operation of addition mod 2. The exclusive-or of any value with itself vanishes, x⊕x = 0, since the arguments have an even number of whatever value x has. Its digital electronics symbol is shown in Figure 2, being a hybrid of the disjunction symbol and the equality symbol. The latter reflects the fact that the negation (which is also the dual) of XOR, ¬(x⊕y), is logical equivalence, EQV, being true just when x and y are equal, either both true or both false. XOR and EQV are the only binary Boolean operations that are commutative and whose truth tables have equally many 0s and 1s. Exclusive-or together with conjunction constitute yet another complete basis for Boolean algebra, with the Boolean operations reformulated as the Zhegalkin polynomials.

Another example is Sheffer stroke, x|y, the NAND gate in digital electronics, which is false when both arguments are true, and true otherwise. NAND is definable by composition of negation with conjunction as x |y = ¬(x∧y). It does not have its own schematic symbol as it is easily represented as an AND gate with an inverted output. Unlike conjunction and disjunction, NAND is a binary operation that can be used to obtain negation, via the definition ¬x = x|x. With negation in hand one can then in turn define conjunction in terms of NAND via x∧y = ¬(x|y), from which all other Boolean operations of nonzero arity can then be obtained. NOR, ¬(x∨y), as the evident dual of NAND serves this purpose equally well. This universal character of NAND and NOR makes them a popular choice for gate arrays, integrated circuits with multiple general-purpose gates.

The above-mentioned duality of conjunction and disjunction is exposed further by De Morgan's laws, ¬(x∧y) = ¬x∨¬y and ¬(x∨y) = ¬x∧¬y. Figure 3 illustrates De Morgan's laws by giving for each gate its De Morgan dual, converted back to the original operation with inverters on both inputs and the outputs. In the case of implication, taking the form of an OR-gate with one inverter on disjunction, that inverter is cancelled by the second inverter that would have gone there. The De Morgan dual of XOR is just XOR with an inverter on the output (there is no separate symbol); as with implication, putting inverters on all three ports cancels the dual's output inverter. More generally, changing an odd number of inverters on an XOR gate produces the dual gate, an even number leaves the gate's functionality unchanged.

As with all the other laws in this section, De Morgan's laws may be verified case by case for each of the 2n possible valuations of the n variables occurring in the law, here two variables and hence 22 = 4 valuations. De Morgan's laws play a role in putting Boolean terms in certain normal forms, one of which we will encounter later in the section on soundness and completeness.

Figure 4 illustrates the corresponding Venn diagrams for each of the four operations presented in Figures 1-3. The interior (respectively exterior) of each circle represents the value true (respectively false) for the corresponding input, x or y. The convention followed here is to represent the true or 1 outputs as dark regions and false as light, but the reverse convention is also sometimes used.

All Boolean operations

There are infinitely many expressions that can be built from two variables using the above operations, suggesting great expressiveness. Yet a straightforward counting argument shows that only 16 distinct binary operations on two values are possible. Any given binary operation is determined by its output values for each possible combination of input values. The two arguments have 2 × 2 = 4 possible combinations of values between them, and there are 24 = 16 ways of assigning an output value to each of these four input values. The choice of one of these 16 assignments then determines the operation; so all together there are only 16 distinct binary operations.

The 16 binary Boolean operations can be organized as follows:

Two constant operations, 0 and 1.

Four operations dependent on one variable, namely x, ¬x, y, and ¬y, whose truth tables amount to two juxtaposed rectangles, one containing two 1s and the other two 0s.

Two operations with a "checkerboard" truth table, namely XOR and EQV.

Four operations are obtained from disjunction with some subset of its inputs negated, namely x∨y, x→y, y→x, and x|y; their truth tables contain a single 0.

The final four come from the same treatment applied to conjunction, having a single 1 in their truth tables.

10 of the 16 operations depend on both variables; all are representable schematically as an AND-gate, an OR-gate, or an XOR-gate, with one port optionally inverted. For the AND and OR gates the location of each inverter matters, for the XOR gate it does not, only whether there is an even or odd number of inverters.

Operations of other arities are possible. For example the ternary counterpart of disjunction can be obtained as (x∨y)∨z. In general an n-ary operation, one having n inputs, has 2n possible valuations of those inputs. An operation has two possibilities for each of these, whence there exist 22n n-ary Boolean operations. For example, there are 232 = 4,294,967,296 operations with 5 inputs.

Although Boolean algebra confines attention to operations that return a single bit, the concept generalizes to operations that take n bits in and return x bits instead of one bit. Digital circuit designers draw such operations as suitably shaped boxes with n wires entering on the left and m wires exiting on the right. Such multi-output operations can be understood simply as m n-ary operations. The operation count must then be raised to the m-th power, or, in the case of n inputs, (22n)m = 2m2n operations. The number of Boolean operations of this generalized kind with say 5 inputs and 5 outputs is 1.46 × 1048. A logic gate or computer module mapping 32 bits to 32 bits could implement any of 5.47 × 1041,373,247,567 operations, more than is obtained by squaring a googol 28 times.

Laws

Axioms

With values and operations in hand, the next aspect of Boolean algebra is that of laws or properties. As with many kinds of algebra, the principal laws take the form of equations between terms built up from variables using the operations of the algebra. Such an equation is deemed a law or identity just when both sides have the same value for all values of the variables, equivalently when the two terms denote the same operation.

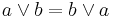

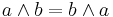

Numeric algebra has laws such as commutativity of addition and multiplication, x + y = y + x and xy = yx. Similarly, Boolean algebra has commutativity in that x ∨ y = y ∨ x for disjunction and x ∧ y = y ∧ x for conjunction. Not all binary operations are commutative; Boolean implication is not commutative, like subtraction and division.

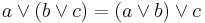

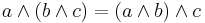

Another equally fundamental law is associativity, which in the case of numeric multiplication is expressed as x(yz) = (xy)z, justifying abbreviating both sides to xyz and thinking of multiplication as a single ternary operation. All four of numeric addition and multiplication and logical disjunction and conjunction are associative, giving for the latter two the Boolean laws x ∨ (y ∨ z) = (x ∨ y) ∨ z and x ∧ (y ∧ z) = (x ∧ y) ∧ z.

Again numeric subtraction and logical implication serve as examples, this time of binary operations that are not associative. On the other hand exclusive-or, being just addition mod 2, is both commutative and associative.

Boolean algebra does not completely mirror numeric algebra however, as both conjunction and disjunction satisfy idempotence, expressed respectively as x ∧ x = x and x ∨ x = x. These laws are easily verified by considering the two valuations 0 and 1 for x. But since 2 + 2 = 2 × 2 = 4 in arithmetic, clearly numeric addition and multiplication are not idempotent. With arithmetic mod 2 on the other hand, multiplication is idempotent, though not addition since 1 + 1 = 0 mod 2, reflected logically in the idempotence of conjunction but not of exclusive-or.

A more subtle difference between number and logic is with x(x + y) and x + xy, neither of which equal x numerically. In Boolean algebra however, both x ∧ (x ∨ y) and x ∨ (x ∧ y) are equal to x, as can be verified for each of the four possible valuations for x and y. These two Boolean laws are called the laws of absorption. These laws (both are needed) together with the associativity, commutativity, and idempotence of conjunction and disjunction constitute the defining laws or axioms of lattice theory. (Actually idempotence can be derived from the other axioms.)

Another law common to numbers and truth values is distributivity of multiplication over addition, when paired with distributivity of conjunction over disjunction. Numerically we have x(y + z) = xy + xz, whose Boolean algebra counterpart is x ∧ (y ∨ z) = (x ∧ y) ∨ (x ∧ z). On the other hand Boolean algebra also has distributivity of disjunction over conjunction, x ∨ (y ∧ z) = (x ∨ y) ∧ (x ∨ z), for which there is no numeric counterpart, consider 1 + 2 × 3 = 7 whereas (1 + 2) × (1 + 3) = 12. Like associativity, distributivity has three variables and so requires checking 23 = 8 cases.

Either distributivity law for Boolean algebra entails the other. Adding either to the axioms for lattices axiomatizes the theory of distributive lattices. That theory does not need the idempotence axioms because they follow from the six absorption, distributivity, and associativity laws.

Two Boolean laws having no numeric counterpart are the laws characterizing logical negation, namely x ∧ ¬x = 0 and x ∨ ¬x = 1. These are the only laws thus far that have required constants. It then follows that x ∧ 0 = x ∧ (x ∧ ¬x) = (x ∧ x) ∧ ¬x = x ∧ ¬x = 0, showing that 0 works with conjunction in logic just as it does with multiplication of numbers. Also x ∨ 0 = x ∨ (x ∧ ¬x) = x by absorption. Dualizing this reasoning, we obtain x ∨ 1 = 1 and x ∧ 1 = x. Alternatively we can justify these laws more directly simply by checking them for each of the two valuations of x.

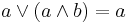

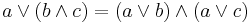

The six laws of lattice theory along with these first two laws for negation axiomatize the theory of complemented lattices. Including either distributivity law then axiomatizes the theory of complemented distributive lattices. For convenience we collect these nine laws in one place as follows.

-

-

associativity

commutativity

absorption

distributivity

complements

-

The next two sections show that this theory is sufficient to axiomatize all the valid laws or identities of two-valued logic, that is, Boolean algebra. It follows that Boolean algebra as commonly defined in terms of these axioms coincides with the intuitive semantic notion of the valid identities of two-valued logic.

Derivations

While the Boolean laws enumerated in the previous section are certainly highlights of Boolean algebra, they by no means exhaust the laws, of which there are infinitely many, nor do they even exhaust the highlights. As it is out of the question to proceed in the ad hoc way of the preceding section for ever, the question arises as to how best to present the remaining laws.

One way of establishing an equation as being a law is to verify its truth for all valuations of its variables, sometimes called the method of truth tables. This is the method we depended on in the previous section to justify each law as we introduced it, constituting the semantic approach to establishing laws. From a practical standpoint the method lends itself to computer implementation for 20-30 variables because the enumeration of valuations is straightforward to program and boring to carry out, making it ideal work for a computer. Because there are 2n valuations to check the method starts to become impractical as 40 variables is approached. Beyond that the approach becomes of value mainly as the in-principle semantic definition of what constitutes an identically true or valid equation.

In contrast the syntactic approach is to derive new laws by symbolic manipulation from already established laws such as those listed in the previous section. (This is not to imply that derivations of a law shorter than the length of a semantic verification of that law need exist, although some thousand-variable laws impossible to verify by enumeration of valuations can have quite short derivations.) Here is an example showing the derivation of (w∨x)∨(y∨z) = (w∨y)∨(x∨z) from just the commutativity and associativity of disjunction.

(w∨x)∨(y∨z)

= ((w∨x)∨y)∨z

= (w∨(x∨y))∨z

= (w∨(y∨x))∨z

= ((w∨y)∨x)∨z

= (w∨y)∨(x∨z)

The first two and last two steps appealed to associativity while the middle step used commutativity.

The rules of derivation for forming new laws from old can be assumed to be those permissible in high school algebra. For definiteness however it is worthwhile formulating a well-defined set of rules showing exactly what is needed. These are the domain-independent rules of equational logic, as sound for logic as they are for numerical domains or any other kind.

Reflexivity: t = t. That is, any equation whose two sides are the same term t is a law. (While arguably an axiom rather than a rule since it has no premises, we classify it as a rule because like the other three rules it is domain-independent, making no mention of specific logical, numeric, or other operations.)

Symmetry: From s = t infer t = s. That is, the two sides of a law may be interchanged. Intuitively one attaches no importance to which side of an equation a term comes from.

Transitivity: A chain s = t = u of two laws yields the law s = u. (This law of "cutting out the middleman" is applied four times in the above example to eliminate the intermediate terms.)

Substitution: Given two laws and a variable, each occurrence of that variable in the first law may be replaced by one or the other side of the second law. (Distinct occurrences can be replaced by distinct sides, but every occurrence must be replaced by one or the other side.)

While the first equation in the above example might seem simply a straightforward application of the associativity law, when analyzed more carefully according to the above rules it can be seen to require something more. We can justify it in terms of the reflexivity and substitution rules. Beginning with the laws x∨(y∨z) = (x∨y)∨z and w∨x = w∨x, we use substitution to replace both occurrences of x by w∨x to arrive at the first equation. All five equations in the chain are accounted for along similar lines, with commutativity in place of associativity in the middle equation.

Soundness and completeness

It can be shown that the two approaches, semantic and syntactic, to constructing all the laws of Boolean algebra lead to the same set of laws. We say that the syntactic approach is sound when it yields a subset of the semantically obtained laws, and complete when it yields a superset thereof. We can then restate this coinciding of the semantic and syntactic approaches as the soundness and completeness of the syntactic approach with respect to (or as calibrated by) the semantic approach.

Soundness follows firstly from the fact that the initial laws or axioms we started from were all identities, that is, semantically true laws. Secondly it depends on the easily verified fact that the rules preserve identities.

Completeness can be proved by first deriving a few additional useful laws and then showing how to use the axioms and rules to prove that a term with n variables, ordered alphabetically say, is equal to its n-ary normal form, namely a unique term associated with the n-ary Boolean operation realized by that term with the variables in that order. It then follows that if two terms denote the same operation (the same thing as being semantically equal), they are both provably equal to the normal form term denoting that operation, and hence by transitivity provably equal to each other.

There is more than one suitable choice of normal form, but complete disjunctive normal form will do. A literal is either a variable or a negated variable. A disjunctive normal form (DNF) term is a disjunction of conjunctions of literals. (Associativity allows a term such as x∨(y∨z) to be viewed as the ternary disjunction x∨y∨z, likewise for longer disjunctions, and similarly for conjunction.) A DNF term is complete when every disjunct (conjunction) contains exactly one occurrence of each variable, independently of whether or not the variable is negated. Such a conjunction uniquely represents the operation it denotes by virtue of serving as a coding of those valuations at which the operation returns 1. Each conjunction codes the valuation setting the positively occurring variables to 1 and the negated ones to 0; the value of the conjunction at that valuation is 1, and hence so is the whole term. At valuations corresponding to omitted conjunctions, all conjunctions present in the term evaluate to 0 and hence so does the whole term.

In outline the general technique for converting any term to its normal form, or normalizing it, is to use De Morgan's laws to push the negations down to the variables. This yields monotone normal form, a term built from literals with conjunctions and disjunctions. For example ¬(x ∨ (¬y∧z)) becomes ¬x ∧ ¬(¬y∧z) and then ¬x ∧ (¬¬y∨¬z). Applying ¬¬x = x then yields ¬x ∧ (y∨¬z).

Next use distributivity of conjunction over disjunction to push all conjunctions down below all disjunctions, yielding a DNF term. This makes the above example (¬x∧y) ∨ (¬x∧¬z).

Then for each variable y, replace each conjunction x not containing y with the disjunction of two copies of x, with y conjoined to one copy of x and ¬y conjoined to the other, in the end yielding a complete DNF term. (This is one place where an auxiliary law helps, in this case x = x∧1 = x∧(y∨¬y) = (x∧y) ∨ (x∧¬y).) In the above example the first conjunction lacks z while the second lacks y; expanding appropriately yields the complete DNF term (¬x∧y∧z) ∨ (¬x∧y∧¬z) ∨ (¬x∧¬z∧y) ∨ (¬x∧¬z∧¬y).

Next use commutativity to put the literals in each conjunction in alphabetical order. The example becomes (¬x∧y∧z) ∨ (¬x∧y∧¬z) ∨ (¬x∧y∧¬z) ∨ (¬x∧¬y∧¬z). This brings any repeated copies of literals next to each other; delete the redundant copies using idempotence of conjunction, not needed in our example.

Lastly order the disjuncts according to a suitable uniformly applied criterion. The criterion we use here is to read the positive and negative literals of a conjunction as respectively 1 and 0 bits, and to read the bits in a conjunction as a binary number. In our example the bits are 011, 010, 010, 000, or in decimal 3, 2, 2, 0. Ordering them numerically as 0, 2, 2, 3 yields (¬x∧¬y∧¬z) ∨ (¬x∧y∧¬z) ∨ (¬x∧y∧¬z) ∨ (¬x∧y∧z). Note that these bits are exactly those valuations for x, y, and z that satisfy our original term ¬(x∨(¬y∧z)). Complete DNF amounts to a canonical way of representing the truth table for the original term as another term.

Repeated conjunctions can then be deleted using idempotence of disjunction, which simplifies our example to (¬x∧¬y∧¬z) ∨ (¬x∧y∧¬z) ∨ (¬x∧y∧z).

In this way we have proved that the term we started with is equal to the normal form term for the operation it denotes. Hence all terms denoting that operation are provably equal to the same normal form term and hence by transitivity to each other.

See also

- Boolean algebra (introduction)

- Boolean algebra (structure)

- Boolean algebra topics

- Boolean domain

- Boolean function

- Boolean parser functions

- Boolean-valued function

- Finitary boolean function

- Heyting algebra

- Lattice (order)

- Laws of Form

- Lindenbaum–Tarski algebra

- Logic minimization

- Logic gate

- Logical graph

- Minimal negation operator

- Propositional calculus

- Truth table

- Universal algebra

- Venn diagram

- Ternary logic

References

- Boole, George (2003) [1854]. An Investigation of the Laws of Thought. Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1-59102-089-9.

- Dwinger, Philip (1971). Introduction to Boolean algebras. Würzburg: Physica Verlag.

- Givant, Steven; Halmos, Paul (2009). Introduction to Boolean Algebras. Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics, Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-40293-2.

- Koppelberg, Sabine (1989). "General Theory of Boolean Algebras". Handbook of Boolean Algebras, Vol. 1 (ed. J. Donald Monk with Robert Bonnet). Amsterdam: North Holland. ISBN 978-0-444-70261-6.

- Peirce, Charles Sanders (1989). Writings of Charles S. Peirce: A Chronological Edition: 1879–1884 (ed. Christian J. W. Kloesel). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-37204-8.

- Schröder, Ernst (1890–1910). Vorlesungen über die Algebra der Logik (exakte Logik), I–III. Leipzig: B.G. Teubner.

- Shannon, Claude (1938). "The Symbolic Analysis of Relay and Switching Circuits". Trans. Am. Inst. Electrical Eng. 38: 713.

- Shannon, Claude (1949). "The Synthesis of Two-Terminal Switching Circuits". Bell System Technical Journal 28: 59–98.

- Sikorski, Roman (1969). Boolean Algebras (3/e ed.). Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-04469-9.

- Stone, Marshall (1936). "The Theory of Representations for Boolean Algebras". Transactions of the American Mathematical Society (Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, Vol. 40, No. 1) 40 (1): 37–111. doi:10.2307/1989664. ISSN 0002-9947. http://jstor.org/stable/1989664.

- Tarski, Alfred (1929). "Sur les classes closes par rapport à certaines opérations élémentaires". Fundamenta Mathematicae 16: 195–197. ISSN 0016-2736.

- Tarski, Alfred (1935). "Zur Grundlegung der Booleschen Algebra, I". Fundamenta Mathematicae 24: 177–198. ISSN 0016-2736.

- Vladimirov, D.A. (1969). булевы алгебры (Boolean algebras, in Russian, German translation Boolesche Algebren 1974). Nauka (German translation Akademie-Verlag).

- Zhegalkin, Ivan Ivanovich (1927). "On the Technique of Calculating Propositions in Symbolic Logic". Mat. Sb 43: 9–28.

External links

- George Boole, 1848, "The Calculus of Logic," Cambridge and Dublin Mathematical Journal III: 183-98.

- Logical Formula Evaluator (for Windows), a software which calculates all possible values of a logical formula

- How Stuff Works - Boolean Logic

- Maiki & Boaz BDD-PROJECT, a Web Application for BDD reduction and visualization.

|

|||||||||||